Route to Repentance

Sermon Parashat Nitzavim 2017

Rabbi Esther Hugenholtz

Route to Repentance

“If you don’t stand for anything, you will fall for

everything.”

It’s a pithy little saying that I read somewhere this

past week. Don’t ask me where or in what context. All that I remember is that

it really stuck with me.

For those of us in Ashkenazi-majority communities, this

is the Shabbat of Selichot. Tonight, we will reconvene to study, sing, reflect

and pray together as we welcome the Yamim Nora’im. Rosh haShanah is only five

days away and it speaks to the ingenious calendar planning of ‘chaz”al’ – our

sages of blessed memory – that parashat Nitzavim and Rosh haShanah line up the

way they do. The Rabbis put incredible thought into calibrating our liturgical

calendar and superimposed the weekly Torah readings on top of it. I believe

that their choices were intentional; the calendar is a wheel that takes you

through the year; which in turn takes us through life. There is a sacred

cadence to our calendar, from the lull just after Simchat Torah and Parashat

B’reishit all the way to the heart of the High Holidays and V’zot ha’Brachah.

We witness the pinpoint of Creation all the way to Moses’ last stirring song,

only to begin again.

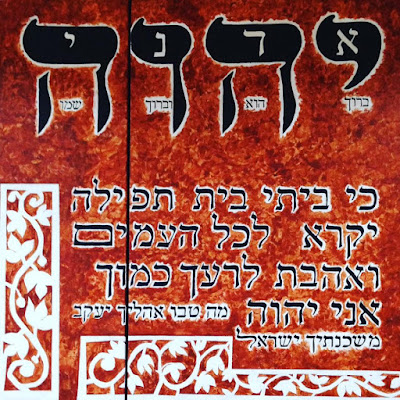

Nitzavim is a powerful parashah and it should be special

to this congregation too. One of the most striking features of this synagogue

that has caught my eye are the beautiful ‘Shiviti’-like paintings on the

removable wall. There is so much love, tenderness and devotion with which these

Hebrew verses were painted and as I let my eyes scan them, I found them

intensely moving. A ‘Shiviti’ is a Hebrew verse in illustrated form (often from

Psalm 16:8, ‘Shiviti Adonai lenegdi tamid’ – ‘I will set the Eternal

before me always’) which invites the worshipers to contemplation. Our

hand-painted Shivitis contain some of Tanakh’s ‘Greatest Hits’ from Psalms, the

Prophetic literature and the Torah.

The High Holidays are the perfect opportunity for us to

contemplate what we stand for. We literally do a great deal of standing (as

well as sitting, bowing and even prostrating) if we are able. But the shofar

blast calls us in more powerful, metaphorical ways too. What do we stand for?

What makes us get up in the morning? What values would we be prepared to fight

for? Each of us will have a private, internal answer to this question but we

might also begin to think about what this means for us as a community in transition.

The Parashah’s name ‘Nitzavim’ comes from the verb ‘lehatziv’,

which means to stand or station oneself. It is a hif’il verb (like ‘lehadlik’,

to light) meaning it is causative. It is not a passive standing, for which the

ordinary verb ‘la’amod’ would suffice, but an active, engaged, empowered

standing. When Moses delivers the message that ‘you stand this day, all of

you’, it is a message of empowerment and inclusivity, but also of

responsibility. All of us shall stand, regardless of our background or status.

And all of us should stand today: not just during the so-called historical

timeframe that the Torah illustrates, but now, right before Rosh haShanah,

before the Gates of Repentance open and close, before the New Year and all its

hopes and perils is ushered in. We are, in a sense, invited to make our

covenant anew, to consider our choice to be Jewish, feel Jewish, act Jewish,

think Jewish, engage with our heritage, by birth or through choice.

Luckily, the Parashah doesn’t leave us hanging. If we

superimpose a template of this Season of Repentance upon this week’s Torah

reading, then our text is not just ancient narrative but becomes a roadmap for

repentance.

We are encouraged to reorient our priorities. We start

off with the gold standard of Jewish ethics: that each person is of equal value

and created in the image of God, no matter our current social positioning. The

Talmud, imagining a sage’s life-after-death experience, reports what the sage

in question (a certain Rav Yosef) saw: ‘I saw an upside-down world. Those who

are on top here are on the bottom there; and those who are here regarded as

lowly are exalted in Heaven.” (Masechet Pesachim 50a). This is the spirit of ‘atem

nitzavim hayom kulchem lifnei Adonai’.

From this ethic, flows uncompromising monotheism. God

demands fealty; and it is complex and hard but valuable and important.

Monotheism trains us in loyalty and commitment; in holding fast onto our core

values and cherishing our identity and integrity. We are reminded of the dire

consequences if we break our covenant. Most of us would not embrace a causal,

determinist theology but the lesson still stands. If you don’t stand for

anything; you will fall for everything. We are called to examine and destroy

the false idols that we erect in the chambers of our hearts: anger, pride,

jealousy, hatred – all those emotions that detract us from seeing the Divine in

ourselves and each other. We have to clear out the emotional rubble before the

Yamim Nora’im and rededicate our inner temples, so that the true work of t’shuvah

can begin.

The parashah pushes on with promise and tenderness. The

reward for t’shuvah is tikkun, repair. We return from our inner and outer exile

and are made whole again. ‘V’shav Adonai Eloheicha… v’richamecha’ –

‘Then the Eternal will take you back in love.’ We are reminded that ‘even if

your outcasts are at the ends of the world, from there the Eternal your God

will gather you’ (Deut. 30:4). This is a message of tender grace amidst the tzuris,

the troubles of life. And lest we think such transformation is beyond our

reach, the Torah makes it very clear: ‘Ki hamitzvah hazot asher anochi

metzav’cha hayom lo niflet hi mimcha vlo r’chokah hi. Lo bashamayim hi.’ –

‘Surely, this Instruction which I enjoin upon you this day is not too baffling

for you, nor is it beyond reach. It is not in the heavens.’

No, it is here, very close to us.

It is within reach and it is possible.

It is now.

Deuteronomy teaches us parallel truths; of beauty and

horror. Of vengeance and forgiveness. It does not sugar-coat the complexity of

life and its difficult relationships and myriad pitfalls. Deuteronomy also

teaches us parallel narratives: the narrative of our people and the narrative

of our own lives. And in all those instances, there is hope, choice and

courage.

We can stand for what we hold to be sacred and true. It

is the beginning of the inner work we are called to do as the great shofar

sounds. May these ancient words – in our Torah and on our walls – be your

guides.

Comments

Post a Comment