Turn, Turn, Turn

Parashat Vayikra/HaChodesh

Rabbi Esther Hugenholtz

Turn, Turn, Turn

How many of you paid attention to yesterday’s solar eclipse? I was getting excited about the whole thing but my physicist husband’s response was surprisingly lackluster: ‘big deal, it’s the moon moving in front of the sun, and that’s that’.

Now, don’t get me wrong: my very scientific husband has an insatiable curiosity and a deep respect for the natural world.

As I pondered his response and realized how very modern it is—not ‘modern’ as in ‘new’, but modern as in embracing a post-Enlightenment, rationalist, empiricist worldview. He is right, of course: all a solar eclipse is the moon blocking the sun.

I trained as a scientist too—a social scientist. And so I’m interested in social phenomena: how have people throughout the ages responded to solar eclipses? With great fear and dread. See, it is only human nature to want to see patterns and omens in Nature and the line between ascribing superstition and imbuing meaning to such patterns is very fine. Even to this day, eclipses inspire powerful superstitions across the world.

Jewish theology and philosophy have little time for superstition. We do not seek false correlations and meaningless causality. But we Jews are experts at drashing – parsing - the world around us for meaning. Seeing patterns may not control our fate or predict our future but it allows us to appreciate and honour life around us. Be it it’s through a solar eclipse, the beauty of the natural world or the majestic turn of the seasons which we record through the rhythms of our sacred calendar.

The month of Nissan is upon us and it is only two weeks until Passover. We could talk about the nitty-gritty of the festival; the cleaning, the cooking, the preparations, the dynamics of family seders, the organization of our Communal Seder. What it means to be a slave and what it means to be free. But I actually want to look at Pesach from a different angle; a top-down perspective. How about looking at Pesach from the perspective of the Jewish calendar and how it all fits in together?

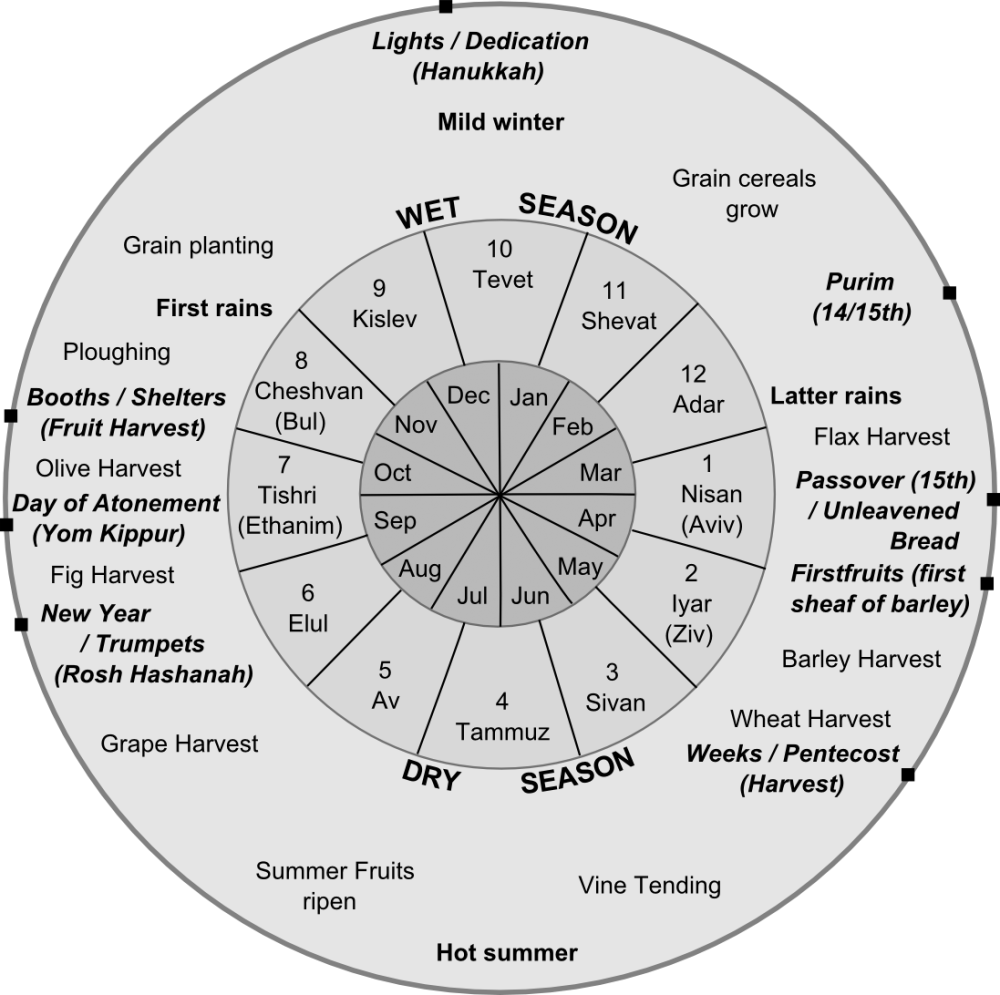

If we imagine the Jewish calendar as a wheel, then some patterns emerge...

|

| [source] |

Passover, the feast of our physical liberation, celebrated in Nissan, is exactly six months away – and hence placed opposite – the month of Tishrey: Rosh haShanah, Yom Kippur and Sukkot, the festivals that celebrate our spiritual liberation—both festivals are close to the Spring and Autumn Equinoxes.

A similar pattern emerges when we look at the Solstices: Kislev in late November or December, close to the Winter Solstice, is the harbinger of Chanukkah, the festival of light in the darkness of oppression through hiding our Jewish identities. Exactly six months later, in the height of early Summer, we celebrate Shavuot, near the Summer Solstice, embracing the idea of light yet again—the light and fire of revelation and proclaiming our Judaism to the world.

And one could even argue that patterns can be drawn across Shevat—think of Tu’bishvat—celebrating the earliest stirrings of renewal all the way to Av—as in Tisha b’Av—where we mourn the destructions experienced by our people.

What can these patterns teach us? They allow us to embrace the natural cadences of life, to cultivate an awareness of the nuances and shades of human experience, the colours and rhythms of nature and history—and how we dare see God therein. The calendar is a blueprint for deeper thinking about our own trajectories.

How will we grow throughout the year?

What are the qualities within our festivals, traditions and selves that we wish to work on?

And what is the connection between Pesach and the High Holy Days?

The connection is more apparent than one might think. In this week’s Parashah, Vayikra, we read in Leviticus 2:11 that we are not to offer leavened products in the Mishkan, the Tabernacle. ‘Kol haMinchah asher takrivu l’Adonai lo ta’aseh chametz ki kol sor v’chol d’vash lo taktiru mimenu isheh l’Adonai’ – ‘Any meal-offering that you offer to the Eternal may not be leavened, for you shall not bring up in smoke any offering of levening or date-honey to the Eternal’.

On the contrary: the ‘breads’ that the Priests offer are to be ‘challot matzah’ – loaves of matzah. We often associate sacrificial bread with challah; we automatically make that connection because of the family table being reconstructed in rabbinic thought as the ‘mishkan me’at’, the small sanctuary of home observance, where fluffy, sweet challah adorns our Shabbat table. Yet, the offerings were unleavened and the Miskhan, and later the Temple, were a permanent chametz-free zone. Within the precincts, the Kohanim kept kosher l’Pesach all year round.

Why?

The following chapters of Vayikra might offer us a clue. As we read about guilt and sin-offerings, the question that the Torah asks is how do we atone for sin? Imagine we fast-forward from Nissan to Tishrey and the question is recast in light of the High Holy Days. As Progressive Jews, we may find little value in the offerings of Leviticus but we find all the more value in the offerings of the heart. Perhaps the holy of holies was a chametz-free zone because of what chametz has come to represent in the Jewish tradition: ego, selfishness, greed. Even the yetzer hara, evil inclination, according to the Ramch”al, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto.

To enter into holy service—however you understand that—means to deflate the ego, to live simply within the rhythms of a moral universe. A tall order for the ancient priests, I’m sure, but certainly possible for one week a year.

Pesach offers us a unique opportunity to spin the wheel of the year towards Redemption.

Maybe this is a good time to ask the question what we are slaves to—literally and figuratively.

Can we scale back?

Can we do without?

Can we eat ‘halachma anya’, the bread of affliction and grow spiritually through that?

Perhaps then we can march towards a meaningful Tishrey, where we’ve done a lot of the inner work of teshuvah, repentance, already. Where we find redemption from guilt and attachment.

Ultimately, patterns are powerful and beautiful things.

It is good to remember that a solar eclipse is ‘just the moon moving in front of the sun’ so that we are not beholden to superstition, that we can embrace rationalism. It is equally important and meaningful to acknowledge the divine rhythms of our universe. We do not need to believe in a God of the gaps Who is pushed back with each new scientific discovery—that’s an untenable theology. Rather, I’d invite you to believe in a God of exquisite patterns, of a universe that can be both rational and mystical, that invites us into feelings of gratitude, beauty and transformation, from of the simplest of experiences such as a piece of unleavened bread to the most sublime alignment of celestial spheres.

Wishing you a meaningful Pesach.

Comments

Post a Comment