Do We Trust The Torah?

Parashat

Mishpatim 2018

Rabbi

Esther Hugenholtz

Can you think of a moment in your life when

you decided to trust the Jewish tradition?

Sharing a personal perspective, I can cast

my mind back to a moment when I was asked to trust a sacred and transformative

moment. It was during my conversion ceremony. Prior to my immersion, I was

asked by my sponsoring rabbi the following, to which I was called to reply.

‘Have you come here of your own free will?’

‘Yes’.

‘Do you pledge allegiance to the God of

Israel?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you pledge allegiance to the Torah of

Israel?’

‘Yes’.

‘And do you pledge allegiance to the People

of Israel?’

‘Yes.’

Answering yes to that triad of questions

was emotionally powerful in a way that transcended the legal underpinnings of

the procedure (even sharing it now still moves me). Of course, establishing

informed consent was a legally binding and necessary act. But it was also something

more. It was a moment of trust. A moment of saying, regardless of what happens,

I will stick with this.

This is where I belong, this is where I

need to be, this is the path that I will walk from now on. For those of you who

are married or have been married, you may be able to relate to that moment of

trust when you pronounced your vows (in some ways, my giyyur, conversion, my chuppah,

wedding and my semikhah, ordination opened

up that same register of transformative trust).

Vows, pledges, promises: plunges of love,

belonging, commitment. Ritual pageantry shapes transitional moments where one

claims agency in order to move into a new space, a new reality, a new place of

belonging. A new identity and perhaps in some way, a new self.

If that sounds a little intense, well, good

– it’s meant to. Liminal, transitional moments are ‘intense’ to downright

frightening which explains why so many cultures use ritualized decoys to contain

the vulnerability of that moment.

My sermon last Shabbat dealt with

Revelation and the Exodus in terms of science, history and meaning. Citing Dr.

Richard Elliot Friedman’s new book on the Exodus, I aimed to make a rationalist

argument in defense of the Torah and its message. Perhaps the Exodus really

happened, albeit in a different way than we expected. In any case, my argument

went, there are compelling reasons to accept the values we derive from such an

event, be it historical or symbolic.

It is a fine and coherent argument but I

now would like us to transcend it and take it in a different direction.

Mishpatim deals with the aftermath of

Revelation. The fires have died down and the dust has settled, the tones of the

shofar have faded. The magic of the experience has evaporated; what remains is

the memory and its emotional import. Mishpatim is a Torah portion that strives

to do different things. On one level, it performs a hermeneutical dance of what

the Rabbis would call ‘klal u’frat’, from the general to the specific. If the Aseret haDibbrot (Ten Commandments) represented

ten general principles, then the legal material of Mishpatim unpacks and

interprets them in specific, concrete ways. How we treat the vulnerable in our

society, those who dwell on the periphery. How we legislate justice. How we

safeguard the principles and integrity of monotheism.

Then there’s the other face of Mishpatim:

the mystical. There’s a strange scene where Moses and Aaron, and Aaron’s son’s

Nadav and Avihu (not his other two, Elazar and Itamar, which is telling if you

want to cast your minds to Parashat Shemini in Leviticus) go up the mountain

with seventy elders of the Israelites and see God in stunning, Technicolor

detail. They eat, drink and celebrate in a vision that is strange and esoteric.

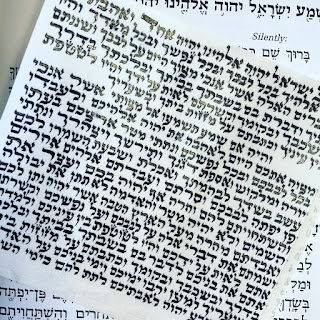

‘Vaya’al

Moseh v’Aharon Nadav v’Avihu v’shiv’im miziknei Yisrael. Vayiru et Elohei

Yisrael v’tachat raglav ke’ma’aseh livnot hasapir uch’etzem hashamayim latahor.’

– ‘And Moses, Aaron, Nadav and Avihu and

seventy of the elders of the Israelites ascended. They saw the God of Israel

and beneath His feet, there was the working of stones of lapis lazuli like the

core of the purest heavens.’ (Ex. 24:9-10) (My translation).

Of course, such an anthropomorphic

description of the Divine encounter makes us uncomfortable – it certainly did

make the Rambam (Maimonides) uncomfortable who considered this envisioning of

God an intellectual rather a sensory experience. Even so, it is a telling

narrative that splits the soul of Mishpatim into two: the legal versus the

mystical, the rational versus the esoteric, the ethical versus the

experiential. Sitting as a fulcrum between these two readings of the portion

sits a passage that balances those opposites. Before Moses and his companions

enjoy their mystical experience, they and all the people at the foot of the

mount affirm the covenant after Revelation by bringing offerings – one for each

of the twelve tribes – and by taking a ‘sefer habrit’, a book (or record, or

perhaps deed or contract) of the covenant and read it aloud to the people (not

unlike a marriage license, a conversion certificate or a naturalization

document). ‘Kol asher diber Adonai

na’aseh v’nishmah’ they famously pronounced. ‘All that the Eternal has

said, we will do and we will hear.’

One could expound famously and thoroughly

on this one line alone. What I would like to focus on, however, is the element

of trust. The Israelites took the plunge (quite literally, according to the

Talmud in Tractate Yevamot 46, since the entire people immersed in a mikveh and

‘converted’ at the moment of Revelation). They didn’t look for symbolic meaning

or historical fact, like we did last week. They took an emotional risk. They

said a full-throated, whole-hearted yes, without having full knowledge of all

the consequences. Indeed this liminal, transitional moment is a scary one.

There is something profoundly

counter-cultural to this. As I mentioned during one of my Rosh haShanah sermons

on surrender, we as modern human beings like being in control. Trust doesn’t

come naturally to us and with good reason. There is a place for skeptical

inquiry and evidence-based scrutiny. But there’s also a place for trust, for

saying yes. There is a place for us seeking out ‘Elohei Yisrael’ in our own

way, to ‘gaze’ into the deepest core of our universe and ask ourselves, in a

healthy, life-affirming way: how can this holy Torah of ours touch and

transform my life?

How can Torah change our lives?

‘Na’aseh v’nishmah’ teaches us that

sometimes the experiential trumps the rational. We may have to try it before we

can say whether we like it. We may want to open ourselves up to wonder, to

being overcome with the unexpected.

To be receptive to those aspects of the

tradition that mystify us a little, perhaps. To try on a new mitzvah, a new

observance, a new way of seeing the world through the lens of the Jewish

tradition and trusting it to transform us somehow.

As we journey from Revelation onwards in

our annual cycle of reading the Torah, I would invite us to journey together.

To create a space in our lives for Judaism in ways we may not have encountered

it before. To pledge ourselves to a practice of Judaism that is intuitive and

experiential. To set ourselves a new challenge – in whatever way feels

appropriate to each of us – and to be willing to be surprised and delighted of

what this rich tradition can bring us.

Comments

Post a Comment